The Crisis in Thai Buddhism: A Systemic Issue Beyond Scandal

The recent sex scandal involving high-ranking monks has deeply shaken public trust. However, the responses from religious leaders, the government, and the general public have failed to address the core issue. This crisis in Thai Buddhism is not solely about monks and sexual misconduct—it is fundamentally about monks and money. Without tackling this underlying problem, the cycle of scandals and temple corruption will continue.

Sexual misconduct among monks is not a new phenomenon. According to the Buddha’s monastic code, breaking the vow of celibacy results in immediate expulsion from the monastic order. The individual must leave and return to lay life immediately. Yet, the latest scandal reveals a more insidious pattern: supposedly respected monks have lived in deceit and hypocrisy, clinging to their robes not for spiritual reasons but to maintain a steady flow of wealth through ritual fees, donations, titles, and prestige. These monks are not addicted to sex—they are addicted to status and financial gain.

One prominent case that highlights this issue is that of Wirawan Emsawat, known as “Sika Golf.” So far, 13 top monks, many holding senior ranks in the clerical hierarchy, have been defrocked. Police traced over 300 million baht from their bank accounts to hers. She now faces charges of extortion, fraud, and theft. She is currently in prison after being denied bail. Meanwhile, the monks involved have not faced criminal charges. They simply returned to lay life, leaving with their substantial bank accounts intact. Many had maintained long-term relationships with her for years. Under the Vinaya, they were no longer monks, yet they continued to exploit the saffron robes, collecting money until the scandal came to light.

When money and power are not at stake, monks who break their vows quietly leave. But when they are rich and powerful, they resort to deception. What turns high-ranking monks into hypocrites is a system that allows them to accumulate wealth and abuse temple funds without consequence. The women involved are merely a symptom of a deeper problem. Instead of addressing the root cause, the state and the clergy continue to blame “femme fatales,” portraying monks as victims—tricked by women due to inexperience. This is a distraction.

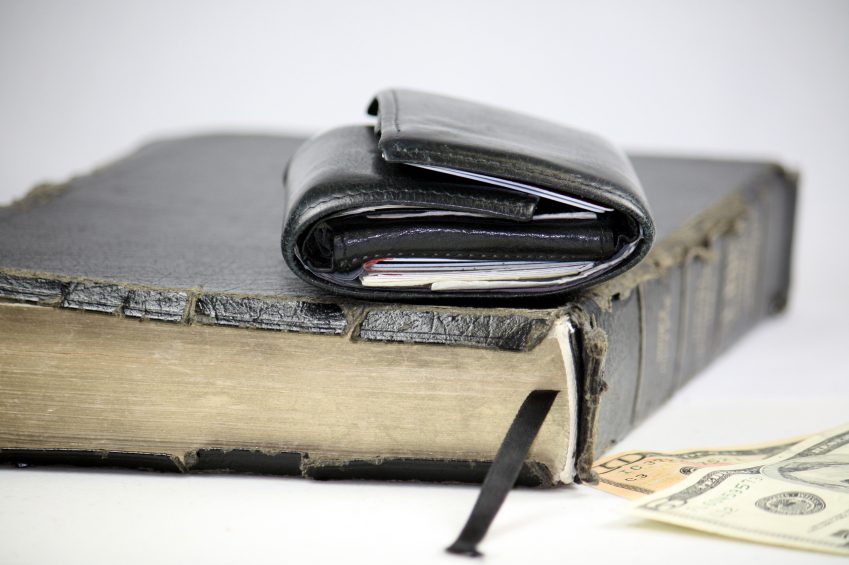

Buddhism teaches that shame is a moral compass. Monks preach this daily. So where was their sense of shame? What dulled their sense of right and wrong? The answer lies in easy money, unmonitored wealth, and the prestige it brings. Temples in Thailand have become big business. The faithful believe that giving to monks earns the highest merit. A study from 15 years ago estimated annual temple donations at over 120 billion baht—a figure likely much higher today.

Despite the Buddha’s prohibition on monks handling money, the monkhood has evolved into a lucrative career. Ritual fees increase with rank, reaching up to 10,000 baht per ceremony. Abbots have complete control over temple finances, and financial reports submitted to the National Office of Buddhism (NOB) are neither audited nor transparent. This lack of oversight creates an environment ripe for abuse.

For poor, rural boys, the monkhood can be a path out of poverty. As they climb the hierarchical structure of the clergy, they gain wealth, respect, and royal-style prestige. Monks then compete to build grander temples to secure promotions. Buying those promotions is an open secret. Temples become theme parks, and faith becomes a transaction. Even the NOB is not immune. Some of its leaders have been caught colluding with abbots to siphon off temple funds.

It is no surprise that monks cling to their robes even after committing serious offenses. The more money involved, the tighter their grip on power. That is why most scandals involve wealthy, high-ranking monks—and why public outrage often misses the mark. The solution is not to shame women or treat rogue monks as isolated cases. Systemic reform is essential.

First, the Sangha Act must be amended to end abbots’ sole control over temple assets. Mandatory audits and community oversight are necessary. A clerical secretariat should oversee recruitment, training, and discipline. Monk education must focus on spiritual development rather than rote scripture memorization. Feudal titles and hierarchies should also be re-evaluated, as they fuel competition for power. Reform must begin where the rot runs deepest: in the clergy’s relationship with money and power.

The faithful, too, must reflect. Blind giving sustains the system. They must question the belief that any man in a robe is “fertile soil” for merit-making and investment in a better next life. Merit should be based on intention and impact—here and now—not on robes and rituals. Blind faith fuels temple corruption and enables “parajika” monks to continue exploiting your belief.

The more you give without question, the more you empower the rot. Reform will not come from the clergy or the state. They benefit from the status quo. Real change begins when the faithful stop feeding a broken system. If the clergy won’t change, the faithful must. Start with your wallet.